How Many Units of a Building Have to Go to Low Income Families

Perspectives on Helping Low-Income Californians Afford Housing

Summary

California has a serious housing shortage. California'southward housing costs, consequently, have been rising apace for decades. These high housing costs go far hard for many Californians to detect housing that is affordable and that meets their needs, forcing them to brand serious trade–offs in order to live in California.

In our March 2015 written report, California's Loftier Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, we outlined the prove for California'south housing shortage and discussed its major ramifications. We also suggested that the key remedy to California's housing challenges is a substantial increase in private home edifice in the country's littoral urban communities. An expansion of California'south housing supply would offer widespread benefits to Californians, also as those who wish to alive in California but cannot afford to do then.

Some fear, nevertheless, that these benefits would not extend to low–income Californians. Considering about new construction is targeted at college–income households, it is often assumed that new construction does not increment the supply of lower–end housing. In addition, some worry that construction of market–rate housing in depression–income neighborhoods leads to displacement of low–income households. In response, some have questioned whether efforts to increase individual housing development are prudent. These observers suggest that policy makers instead focus on expanding authorities programs that aim to help depression–income Californians afford housing.

In this follow up to California's High Housing Costs, we offer additional evidence that facilitating more private housing development in the country'south coastal urban communities would help make housing more affordable for low–income Californians. Existing affordable housing programs assist only a small proportion of depression–income Californians. Well-nigh low–income Californians receive little or no assistance. Expanding affordable housing programs to help these households likely would be extremely challenging and prohibitively expensive. It may be best to focus these programs on Californians with more specialized housing needs—such every bit homeless individuals and families or persons with significant physical and mental health challenges.

Encouraging boosted individual housing construction can help the many depression–income Californians who practise non receive assistance. Considerable prove suggests that construction of market place–rate housing reduces housing costs for low–income households and, consequently, helps to mitigate displacement in many cases. Bringing about more than individual home edifice, however, would be no easy job, requiring state and local policy makers to confront very challenging issues and taking many years to come to fruition. Despite these difficulties, these efforts could provide significant widespread benefits: lower housing costs for millions of Californians.

Back to the Top

Various Government Programs Help Californians Afford Housing

Federal, state, and local governments implement a variety of programs aimed at helping Californians, particularly depression–income Californians, beget housing. These programs more often than not work in one of three ways: (one) increasing the supply of moderately priced housing, (2) paying a portion of households' rent costs, or (three) limiting the prices and rents holding owners may charge for housing.

Various Programs Build New Moderately Priced Housing . Federal, state, and local governments provide direct financial assistance—typically tax credits, grants, or low–cost loans—to housing developers for the construction of rental housing. In substitution, developers reserve these units for lower–income households. (Until recently, local redevelopment agencies also provided this type of fiscal assistance.) Past far the largest of these programs is the federal and state Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), which provides tax credits to affordable housing developers to cover a portion of their building costs. The LIHTC subsidizes the new construction of around 7,000 rental units annually in the state—typically less than 10 percent of total public and private housing construction. This represents a meaning bulk of the affordable housing units synthetic in California each year.

Vouchers Help Households Beget Housing. The federal regime besides makes payments to landlords—known as housing vouchers—on behalf of about 400,000 depression–income households in California. These payments generally cover the portion of a rental unit of measurement'southward monthly toll that exceeds 30 pct of the household's income.

Some Local Governments Place Limits on Prices and Rents. Some local governments take policies that require belongings owners charge beneath–market prices and rents. In some cases, local governments limit how much landlords can increase rents each year for existing tenants. About 15 California cities accept these rent controls, including Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland. In 1995, the state enacted Affiliate 331 of 1995 (AB 1164, Hawkins), which prevented rent control for properties built after 1995 or properties built prior to 1995 that had not previously been subject area to rent control. Assembly Bill 1164 also allowed landlords to reset rents to market rates when properties transferred from one tenant to another. In other cases, local governments require developers of market–rate housing to charge beneath–market prices and rents for a portion of the units they build, a policy chosen "inclusionary housing."

Back to the Top

Demand For Housing Assistance Outstrips Resource

Many Low–Income Households Receive No Help. The number of low–income Californians in need of assistance far exceeds the resources of existing federal, state, and local affordable housing programs. Currently, almost three.three 1000000 low–income households (who earn eighty percent or less of the median income where they live) rent housing in California, including 2.3 meg very–low–income households (who earn fifty percent or less of the median income where they alive). Effectually 1–quarter (roughly 800,000) of low–income households live in subsidized affordable housing or receive housing vouchers. Most households receive no assist from these programs. Those that do often detect that information technology takes several years to get assistance. Roughly 700,000 households occupy waiting lists for housing vouchers, near twice the number of vouchers available.

Majority of Low–Income Households Spend More than Half of Their Income on Housing. Around ane.7 meg depression–income renter households in California written report spending more than one-half of their income on housing. This is about 14 percent of all California households, a considerably higher proportion than in the rest of the country (about viii pct).

Back to the Top

Challenges of Expanding Existing Programs

One possible response to these affordability challenges could be to expand existing housing programs. Given the number of households struggling with high housing costs, however, this arroyo would crave a dramatic expansion of existing government programs, necessitating funding increases orders of magnitude larger than existing program funding and far–reaching changes in existing regulations. Such a dramatic change would face several challenges and probably would have unintended consequences. Ultimately, attempting to address the state's housing affordability challenges primarily through expansion of government programs likely would be impractical. This, however, does not preclude these programs from playing a function in a broader strategy to improve California's housing affordability. Below, we discuss these issues in more particular.

Expanding Aid Programs Would Be Very Expensive

Extending housing assistance to low–income Californians who currently do not receive it—either through subsidies for affordable units or housing vouchers—would crave an almanac funding commitment in the low tens of billions of dollars. This is roughly the magnitude of the land's largest General Fund expenditure outside of education (Medi–Cal).

Affordable Housing Construction Requires Big Public Subsidies. While information technology is difficult to gauge precisely how many units of affordable housing are needed, a reasonable starting point is the state's current population of low–income renter households that spend more than than one-half of their income on housing—about 1.vii million households. Based on data from the LIHTC, housing built for low–income households in California's coastal urban areas requires a public subsidy of effectually $165,000 per unit. At this cost, building affordable housing for California's i.7 million rent encumbered depression–income households would toll in excess of $250 billion. This toll could be spread out over several years (by issuing bonds or providing subsidies to builders in installments), requiring annual expenditures in the range of $fifteen billion to $30 billion. There is a adept chance the actual cost could be higher. Affordable housing projects oft receive subsidies from more than one source, meaning the public subsidy cost per unit likely is higher than $165,000. It is too possible the number of units needed could exist college if efforts to brand California's housing more affordable spurred more people to motion to the state. Conversely, at that place is some chance the cost could be lower if building some portion of the 1.vii one thousand thousand eased competition at the bottom terminate of the housing market and allowed some low–income families to notice affordable marketplace–rate housing. All the same, under whatsoever circumstances information technology is likely this approach would require ongoing almanac funding at least in the low tens of billions of dollars.

Expanding Housing Vouchers Also Would Exist Expensive. Housing vouchers would exist similarly expensive. According to American Customs Survey data, around 2.five million low–income households in California spend more than xxx percentage of their income on rent. These households' rents exceed thirty percent of their incomes by $625 each month on average, meaning they would crave an annual subsidy of around $seven,500. This suggests that providing housing vouchers to all of these households would cost around $20 billion annually. By similar logic, a less generous program that covered rent costs exceeding 50 percent of household income would cost effectually $ten billion annually. In that location is, however, good reason to believe the cost of expanding voucher programs would exist significantly college than these simple estimates suggest. As we talk over in the next section, a major increment in the number of voucher recipients likely would crusade rents to rise. Higher rent costs, in plow, would increase the amount government would need to pay on behalf of low–income renters. This issue is hard to quantify but probably would add several billion to tens of billions of dollars to the annual cost of a major expansion of vouchers.

Existing Housing Shortage Poses Bug for Some Programs

Many housing programs—vouchers, rent control, and inclusionary housing—endeavour to make housing more affordable without increasing the overall supply of housing. This approach does very little to address the underlying cause of California'due south high housing costs: a housing shortage. Any approach that does not accost the state'southward housing shortage faces the following problems.

Housing Shortage Has Downsides Not Addressed by Existing Housing Programs. Loftier housing costs are not the only downside of the land'southward housing shortage. As we discussed in detail in California's High Housing Costs, California'due south housing shortage denies many households the opportunity to live in the state and contribute to the state's economic system. This, in plough, reduces the land's economic productivity. The state's housing shortage also makes many Californians—not simply low–income residents—more than likely to commute longer distances, alive in overcrowded housing, and delay or forgo homeownership. Housing programs such every bit vouchers, rent control, and inclusionary housing that do not add to the state's housing stock do little to address these problems.

Scarcity of Housing Undermines Housing Vouchers. California's tight housing markets pose several challenges for housing voucher programs which tin can limit their effectiveness. In competitive housing markets, landlords often are reluctant to rent to housing voucher recipients. Landlords may not be interested in navigating program requirements or may perceive voucher recipients to be less reliable tenants. One nationwide study conducted in 2001 found that only two–thirds of voucher recipients in competitive housing markets were able to secure housing. This issue probable would be amplified if the number of voucher recipients competing for housing were increased significantly. In addition, some research suggests that expanding housing vouchers in competitive housing markets results in hire increases, which either start benefits to voucher holders or increment government costs for the programme. One written report looking at an unusually large increase in the federal allotment of housing vouchers in the early 2000s found that each 10 percent increase in vouchers in tight housing markets increased monthly rents by an average of $18 (nearly 2 per centum). This suggests that extending vouchers to all of California'south low–income households (a several hundred percent increase in the supply of vouchers) could pb to substantial rent inflation. If this were to occur, the estimates in the prior section of the cost to expand vouchers to all low–income households would be significantly higher.

Housing Costs for Households Non Receiving Assistance Could Rise. Expansion of voucher programs also could beal housing challenges for those who practise non receive assistance, specially if assistance is extended to some, merely not all low–income households. Equally discussed above, research suggests that housing vouchers result in rent aggrandizement. This hire inflation not only furnishings voucher recipients only potentially increases rents paid by other depression– and lower–eye income households that do not receive assistance.

Housing Shortage Likewise Creates Problems for Rent Control Policies. The state'south shortage of housing also presents challenges for expanding rent control policies. Proposals to expand rent control often focus on two broad changes: (1) expanding the number of housing units covered—by applying controls to newer properties or enacting controls in locations that currently lack them—and (2) prohibiting landlords from resetting rents to market rates for new tenants. Neither of these changes would increase the supply of housing and, in fact, likely would discourage new structure. Households looking to motility to California or within California would therefore proceed to confront stiff competition for limited housing, making it hard for them to secure housing that they tin afford. Requiring landlords to accuse new tenants below–market rents would non eliminate this competition. Households would have to compete based on factors other than how much they are willing to pay. Landlords might decide betwixt tenants based on their income, creditworthiness, or socioeconomic status, likely to the benefit of more flush renters.

Barriers to Private Development Also Hinder Affordable Housing Programs

Local Resistance and Ecology Protection Policies Constrain Housing Development. Local community resistance and California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) challenges limit the amount of housing—both individual and subsidized—built in California. These factors present challenges for subsidized construction and inclusionary housing programs. Subsidized housing construction faces the aforementioned, in many cases more, community opposition every bit market–rate housing because it ofttimes is perceived every bit bringing negative changes to a community'south quality or character. Furthermore, subsidized construction, like other housing developments, frequently must undergo the state's environmental review procedure outlined in CEQA. This can add costs and delay to these projects. Inclusionary housing programs rely on individual housing development to fund construction of affordable housing. Because of this, barriers that constrain private housing evolution also limit the corporeality of affordable housing produced by inclusionary housing programs.

Abode Builders Often Forced to Compete for Limited Development Opportunities. With country and local policies limiting the number of housing projects that are permitted, dwelling house builders frequently compete for express opportunities. Ane result of this is that subsidized construction oft substitutes for—or "crowds out"—market place–rate development. Several studies have documented this crowd–out effect, by and large finding that the construction of one subsidized housing unit reduces marketplace–rate structure by one–half to 1 housing unit of measurement. These oversupply–out effects can diminish the extent to which subsidized housing construction increases the state's overall supply of housing.

Other Unintended Consequences

"Lock–In" Effect. Households residing in affordable housing (built via subsidized construction or inclusionary housing) or rent–controlled housing typically pay rents well below market place rates. Because of this, households may exist discouraged from moving from their existing unit to marketplace–rate housing even when it may otherwise do good them—for example, if the market–rate housing would be closer to a new job. This lock–in effect tin can cause households to stay longer in a particular location than is otherwise optimal for them.

Declining Quality of Housing. By depressing rents, rent control policies reduce the income received by owners of rental housing. In response, property owners may attempt to cutting back their operating costs by forgoing maintenance and repairs. Over time, this tin can result in a decline in the overall quality of a customs'south housing stock.

Back to the Top

More Private Home Building Could Help

Most depression–income Californians receive little or no assistance from existing affordable housing programs. Given the challenges of significantly expanding affordable housing programs, this is likely to persist for the foreseeable future. Many low–income households volition go along to struggle to find housing that they can afford. Encouraging more individual housing evolution seems like a reasonable approach to help these households. But would it really assistance? In this department, we present bear witness that construction of new, market–rate housing tin can lower housing costs for low–income households.

Increased Supply, Lower Costs

Lack of Supply Drives High Housing Costs. Equally nosotros demonstrate in California'south Loftier Housing Costs, a shortage of housing results in loftier and ascension housing costs. When the number of households seeking housing exceeds the number of units available, households must try to outbid each other, driving upwardly prices and rents. Increasing the supply of housing tin help alleviate this competition and, in turn, place downwardly pressure on housing costs.

Edifice New Housing Indirectly Adds to the Supply of Housing at the Lower Stop of the Market place. New market–rate housing typically is targeted at higher–income households. This seems to propose that structure of new market–rate housing does not add to the supply of lower–end housing. Edifice new market place–rate housing, withal, indirectly increases the supply of housing available to low–income households in multiple ways.

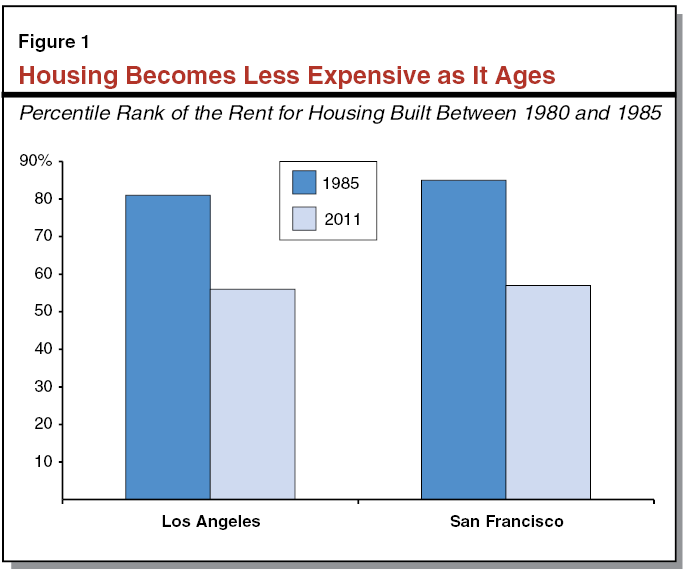

Housing Becomes Less Desirable equally Information technology Ages . . . New housing mostly becomes less desirable as it ages and, every bit a outcome, becomes less expensive over time. Market place–rate housing constructed now volition therefore add to a customs's stock of lower–cost housing in the time to come as these new homes age and go more affordable. Our analysis of American Housing Survey data finds show that housing becomes less expensive every bit information technology ages. Effigy 1 shows the average hire for housing built between 1980 and 1985 in Los Angeles and San Francisco. These housing units were relatively expensive in 1985 (rents in the summit fifth of all rental units) only were considerably more affordable by 2011 (rents about the median of all rental units). Housing that likely was considered "luxury" when first built declined to the eye of the housing marketplace within 25 years.

. . . But Lack of New Construction Can Wearisome This Procedure. When new construction is abundant, centre–income households looking to upgrade the quality of their housing often move from older, more affordable housing to new housing. Every bit these centre–income households move out of older housing information technology becomes available for lower–income households. This is less likely to occur in communities where new housing construction is express. Faced with heightened competition for scarce housing, middle–income households may alive longer in aging housing. Instead of upgrading by moving to a new home, owners of crumbling homes may choose to remodel their existing homes. Similarly, landlords of aging rental housing may elect to update their properties so that they can continue to market them to middle–income households. As a result, less housing transitions to the lower–end of the housing market over time. Ane study of housing costs in the U.S. found that rental housing more often than not depreciated past about two.five per centum per year between 1985 and 2011, but that this charge per unit was considerably lower (ane.8 percent per year) in regions with relatively limited housing supply.

New Housing Construction Eases Competition Between Middle– and Low–Income Households. Some other result of also fiddling housing construction is that more affluent households, faced with limited housing choices, may choose to live in neighborhoods and housing units that historically have been occupied by low–income households. This reduces the corporeality of housing available for low–income households. Diverse economic studies take documented this outcome. One analysis of American Housing Survey information past researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York establish that "the more constrained the supply response for new residential units to demand shocks, the greater the probability that an affordable unit will filter up and out of the affordable stock." Other researchers have found that low–income neighborhoods are more likely to experience an influx of higher–income households when they are in close proximity to affluent neighborhoods with tight housing markets.

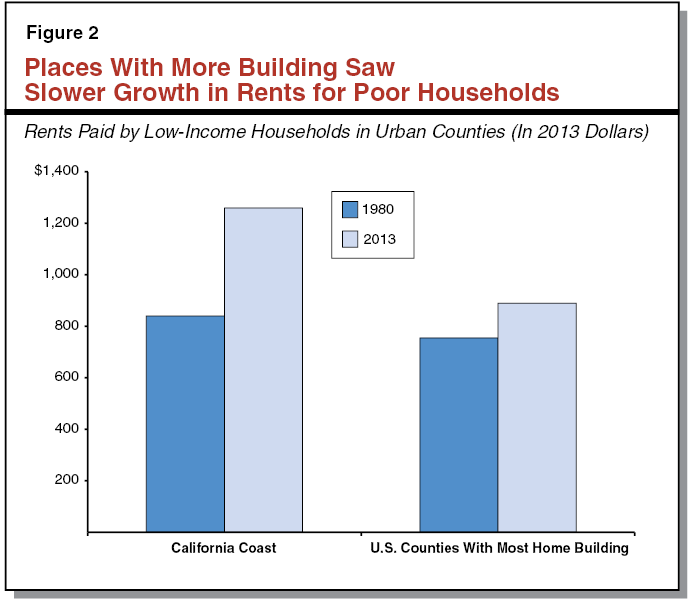

More Supply Places Down Pressure on Prices and Rents. When the number of housing units bachelor at the lower end of a community'south housing market increases, growth in prices and rents slows. Evidence supporting this relationship can exist plant by comparing housing expenditures of depression–income households living in California's boring–growing littoral communities to those living in fast–growing communities elsewhere in the state. Between 1980 and 2013, the housing stock in California's coastal urban counties (counties comprising metropolitan areas with populations greater than 500,000) grew past only 34 percent, compared to 99 percent in the fastest growing urban counties throughout the land (top fifth of all urban counties). As figure 2 shows, over the same time period rents paid by low–income households grew nearly three times faster in California's littoral urban counties than in the fastest growing urban counties (50 percentage compared to xviii percentage). Every bit a result, the typical low–income household in California's costal urban counties now spends effectually 54 percentage of their income on housing, compared to only 43 percent in fast growing counties. This difference—11 percentage points—is roughly equal to a typical low–income household'southward full spending on transportation.

Lower Costs Reduce Chances of Displacement

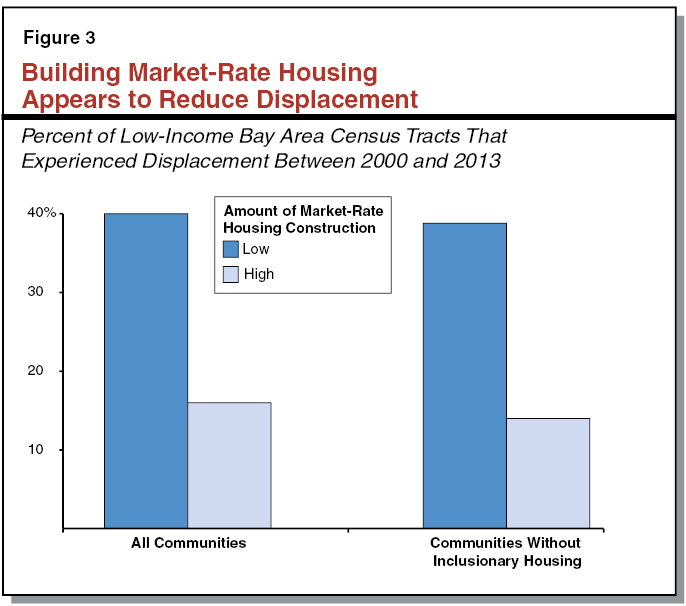

More Individual Evolution Associated With Less Displacement. As marketplace–rate housing construction tends to tedious the growth in prices and rents, it tin can brand it easier for low–income households to afford their existing homes. This can help to lessen the deportation of low–income households. Our assay of low–income neighborhoods in the Bay Area suggests a link between increased construction of market–rate housing and reduced displacement. (Run across the technical appendix for more information on how we defined displacement for this analysis.) Between 2000 and 2013, low–income demography tracts (tracts with an above–boilerplate concentration of low–income households) in the Bay Area that built the most market–charge per unit housing experienced considerably less displacement. Every bit Figure 3 shows, deportation was more twice as probable in low–income census tracts with little market–rate housing construction (lesser 5th of all tracts) than in low–income census tracts with high construction levels (summit fifth of all tracts).

Results Do Not Appear to Exist Driven by Inclusionary Housing Policies. Ane possible explanation for this finding could exist that many Bay Expanse communities have inclusionary housing policies. In communities with inclusionary housing policies, most new market–rate construction is paired with construction of new affordable housing. Information technology is possible that the new affordable housing units associated with increased marketplace–rate development—and not market place–rate development itself—could be mitigating displacement. Our analysis, yet, finds that market–rate housing construction appears to be associated with less displacement regardless of a customs's inclusionary housing policies. As with other Bay Area communities, in communities without inclusionary housing policies, displacement was more than twice as likely in low–income demography tracts with express market–rate housing structure than in low–income census tracts with high construction levels.

Relationship Remains Afterward Accounting for Economic and Demographic Factors. Other factors play a role in determining which neighborhoods experience displacement. A neighborhood's demographics and housing characteristics probably are important. Nonetheless, we continue to discover that increased market–rate housing construction is linked to reduced displacement after using common statistical techniques to business relationship for these factors. (See the technical appendix for more details.)

Back to the Acme

Conclusion

Addressing California's housing crunch is one of the about hard challenges facing the state's policy makers. The scope of the problem is massive. Millions of Californians struggle to find housing that is both affordable and suits their needs. The crisis also is a long time in the making, the culmination of decades of shortfalls in housing structure. And simply as the crisis has taken decades to develop, it will take many years or decades to correct. There are no quick and like shooting fish in a barrel fixes.

The current response to the land's housing crisis oft has centered on how to improve affordable housing programs. The enormity of California's housing challenges, however, suggests that policy makers look for solutions beyond these programs. While affordable housing programs are vitally important to the households they aid, these programs help only a small fraction of the Californians that are struggling to cope with the country's high housing costs. The bulk of depression–income households receive fiddling or no assist and spend more than one-half of their income on housing. Practically speaking, expanding affordable housing programs to serve these households would be extremely challenging and prohibitively expensive.

In our view, encouraging more private housing development can provide some relief to low–income households that are unable to secure assistance. While the office of affordable housing programs in helping California'southward most disadvantaged residents remains important, we suggest policy makers primarily focus on expanding efforts to encourage private housing evolution. Doing so will require policy makers to revisit long–standing country policies on local governance and environmental protection, besides as local planning and land use regimes. The changes needed to bring near significant increases in housing construction undoubtedly will be difficult and will accept many years to come up to fruition. Policy makers should nonetheless consider these efforts worthwhile. In time, such an approach offers the greatest potential benefits to the well-nigh Californians.

Back to the Acme

References

Early, D. Due west. (2000). Rent Control, Rental Housing Supply, and the Distribution of Tenant Benefits. Periodical of Urban Economics, 48(2), 185–204.

Eriksen, M. D., & Rosenthal, Southward. Southward. (2010). Crowd out effects of place–based subsidized rental housing: New evidence from the LIHTC program. Journal of Public Economic science, 94(11), 953–966.

Eriksen, M. D., & Ross, A. (2014). Housing Vouchers and the Price of Rental Housing. American Economic Periodical: Economic Policy.

Finkel, Thousand., & Buron, L. (2001). Study on Section 8 Voucher Success Rates. Volume I. Quantitative Study of Success Rates in Metropolitan Areas. Prepared by Abt Associates for the U.Southward. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2–3.

Glaeser, East. 50., & Luttmer, Due east. F. (2003). The Misallocation of Housing Under Rent Command. The American Economic Review, 93(iv).

Guerrieri, 5., Hartley, D., & Hurst, E. (2013). Endogenous Gentrification and Housing Cost Dynamics. Journal of Public Economics, Book 100 (C), 45–sixty.

Gyourko, J., & Linneman, P. (1990). Rent Controls and Rental Housing Quality: A Note on the Effects of New York City's Old Controls. Journal of Urban Economic science, 27(3), 398–409.

Malpezzi, S., & Vandell, Chiliad. (2002). Does the depression–income housing tax credit increment the supply of housing? Journal of Housing Economics, eleven(4), 360–380.

Munch, J. R., & Svarer, M. (2002). Rent control and tenancy elapsing. Periodical of Urban Economics, 52(iii), 542–560.

Rosenthal, S. South. (2014). Are Individual Markets and Filtering a Viable Source of Low–Income Housing? Estimates from a "Repeat Income" Model. The American Economic Review, 104(2), 687–706.

Sims, D. P. (2007). Out of control: What can we learn from the finish of Massachusetts rent command? Journal of Urban Economics, 61(ane), 129–151.

Sinai, T., & Waldfogel, J. (2005). Practise depression–income housing subsidies increase the occupied housing stock? Journal of Public Economics, 89(11), 2137–2164.

Somerville, C. T., & Mayer, C. J. (2003). Regime Regulation and Changes in the Affordable Housing Stock. Economic Policy Review, nine(ii), 45–62.

Susin, S. (2002). Hire vouchers and the toll of depression–income housing. Journal of Public Economics, 83(one), 109–152.

Dorsum to the Top

Technical Appendix

To examine the relationship between marketplace–rate housing construction and displacement of low–income households we developed a uncomplicated econometric model to estimate the probability of a low–income Bay Area neighborhood experiencing displacement.

Data. We use data (.xlsx) on Bay Area census tracts (small subdivisions of a county typically containing around 4,000 people) maintained past researchers with the University of California (UC) Berkeley Urban Displacement Project. This dataset included information on census tract demographics, housing characteristics, and housing construction levels. We focus on information for the period 2000 to 2013.

Defining Displacement. Researchers take not developed a single definition of displacement. Unlike studies use different measures. For our assay, we use a straightforward all the same imperfect definition of displacement which is like to the definition used by UC Berkeley researchers. Specifically, we define a demography tract as having experienced displacement if (one) its overall population increased and its population of low–income households decreased or (two) its overall population decreased and its low–income population declined faster than the overall population.

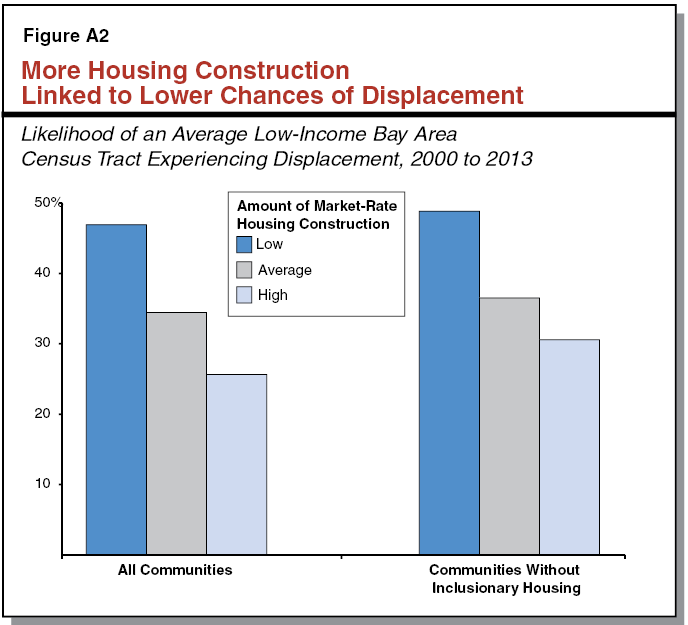

Our Model. We use probit regression analysis to evaluate how various factors affected the likelihood of a census tract experiencing displacement between 2000 and 2013. This type of model allows the states to hold constant various economical and demographic factors and isolate the impact of increased market place–rate construction on the likelihood of deportation. The results of our regression are show in Figure A1. Coefficient estimates from probit regressions are not hands interpreted. While the fact that the coefficient for market–rate housing construction is statistically pregnant and negative suggests that more construction reduces the likelihood of displacement, the magnitude of this effect is not immediately clear. To ameliorate understand these results, we used the model to compare the probability that an average census tract would feel deportation when its market–charge per unit construction was low (0 units), average (136 units), and loftier (243 units). As shown in Figure A2, with low structure levels, a census tract's probability of experiencing displacement was 47 per centum, compared to 34 percent with average construction levels, and 26 pct with high construction levels.

Figure A1

Regression Results

Dependent Variable: Did Displacement Occur (Yes=one and No=0)?

| Independent Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error |

| Number of market–rate housing units built | –0.00237 | 0.00043 |

| Share of population that is low income | one.74075 | 0.54137 |

| Share of population that is nonwhite | –0.61213 | 0.29151 |

| Share of adults over 25 with a college degree | 1.90054 | 0.38599 |

| Population density | –0.00001 | 0.00000 |

| Share of housing built earlier 1950 | i.16506 | 0.22569 |

| Constant | –i.45886 | 0.33420 |

andersonfavered1941.blogspot.com

Source: https://lao.ca.gov/publications/report/3345

0 Response to "How Many Units of a Building Have to Go to Low Income Families"

Post a Comment